What role for Plantations in Climate Adaptation? This is a study tour with a difference.

Gansu province in the north of China was an important stop on the ancient Silk Road – but life here is not silky smooth. The climate is harsh, and the desert encroaches on agricultural land at an increasing rate every year. Desert expansion, land infertility and lack of water threaten the living standards of communities in Gansu.

WWF’s New Generation Plantations (NGP) platform is organizing a study tour in Gansu during May 8-12 together with the China Green Carbon Foundation, Suzano and WWF-China. The NGP study tour aims to support these organizations in finding the tree species which both grow best in desert conditions and enable farmers to sustain their livelihoods.

While few trees thrive in this harsh landscape, one species stands out. Yellowhorn (Xanthus sorbifolium) grows naturally in these desert climates, withstanding the sub-freezing winters and hot summers, and produces oil-rich seeds that can be used in food, cosmetics and as a biofuel. Could this be a potential solution for stabilizing soils, reversing the spread of the desert and providing livelihoods for local people in a water-stressed region?

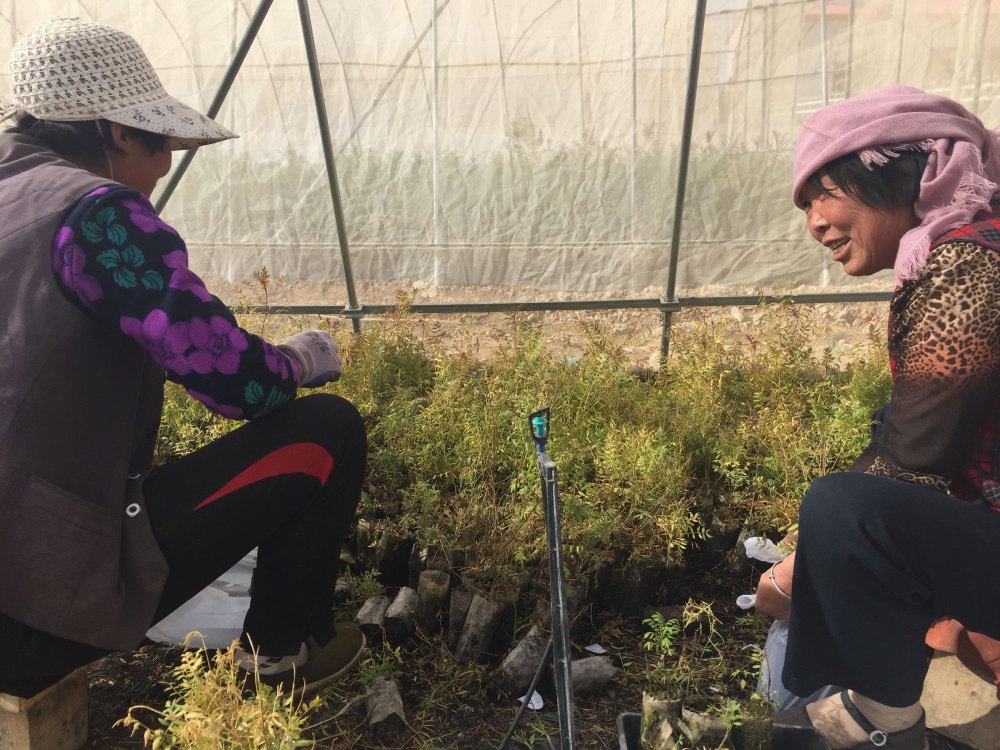

The Chinese State Forest Administration is supporting the planting of 940,000 hectares of yellowhorn trees across China. Suzano, an NGP participant, has established a 14-hectare research, development and seedling production centre for the species in Gansu, which will be one of the places visited by the tour participants.

China Green Carbon Foundation (CGCF) is the first nation-wide non-profit public funding foundation dedicated to combating climate change by increasing carbon sink in China. CGCF was established in 2010, approved by the State Council, was registered at the Ministry of Civil Affairs and operated under the governance of the State Forestry Administration. CGCF provides a platform for enterprises and citizens to fulfil their social responsibility by storing carbon credits mainly through forestry measures. CGCF aims to strengthen the public capacity of combating climate change, to support and perfect the forest ecology benefit compensation mechanism of China through conducting forest carbon sequestration projects and relative social activities.

Gansu province is one of the regions set to benefit from the One Belt One Road initiative – a multi-trillion dollar development strategy proposed by the Chinese government, which aims to link Central Asia with the Middle East, Europe and beyond. NGP hopes the study tour will provide insights that can enhance the sustainability and resilience of this massive project.

This daily blog is written by Barney Jeffries, a participant to the study tour.