When plantation companies invest in a region, it opens up opportunities for small-scale farmers to grow trees to supply the same markets – whether that’s a pulp mill or, in the case of NFC, electricity poles. In the jargon, these independent tree farmers are known as outgrowers.

This morning we visit some outgrowers supported by NFC. Inside a neat plot of three-year-old eucalypts, we divide into groups and have a couple of hours to talk with the growers.

The people we talk to are happy about the opportunity. They see it as a potentially lucrative source of income, say that it’s enhanced their standing in society, and are grateful to NFC for supplying them with seedlings and initial training.

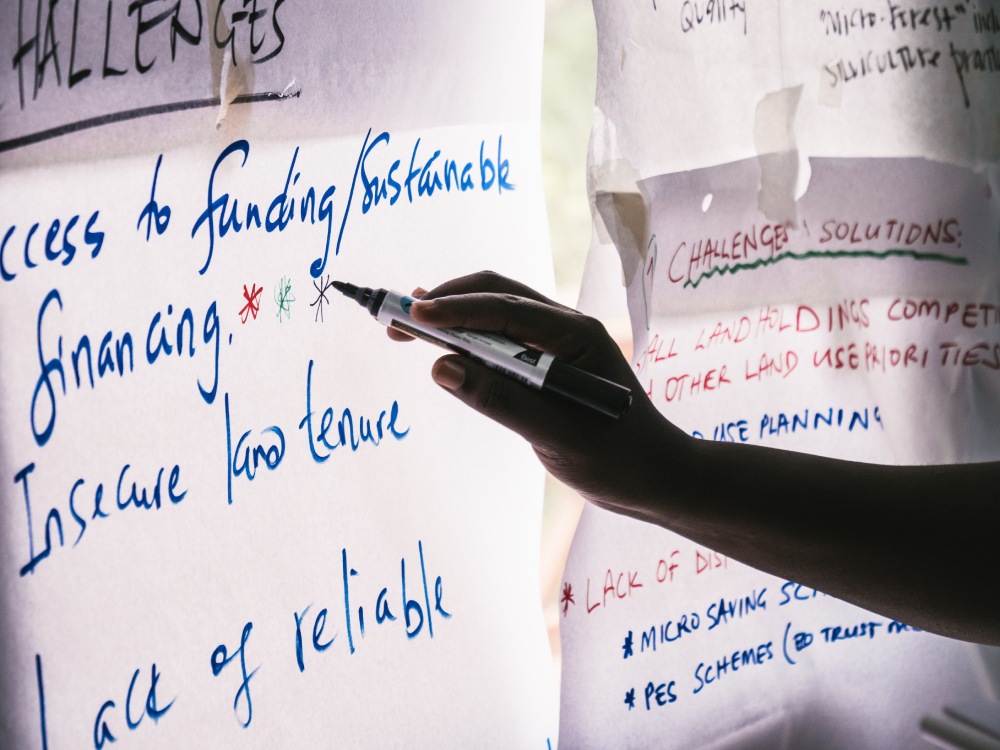

It’s clear, though, that there are challenges, and that things could be improved significantly. Growing eucalyptus trees can be profitable – a quick back-of-envelope calculation suggests farmers can earn at least twice as much from their trees as they would growing maize on the same land. But only if they can afford to wait long enough.

One grower complains that the price he got for his trees was far too low: he sold some of his at seven years old for around a dollar each. If he’d waited another five years, when they’d be suitable for high-grade electricity poles rather than cheap fencing, he could have fetched 30 times that price.

Part of the problem is that some farmers simply can’t wait 12 years to cash in – they have families to support, school fees to pay. Also, many are unaware of the market prices they should be getting, which leaves them vulnerable to middlemen convincing them to sell below market rates.

But these aren’t insurmountable problems. NFC has just appointed a full-time community development officer to work with growers in this area, who should be able to provide the outgrowers with better support and information on both silviculture and markets.

There’s also clearly a role for the growers to work together much more closely through an association or cooperative (NFC and the Uganda Timber Growers Association, also in attendance on this study tour, could help set this up). Working as a collective could give them increased bargaining power, improve sharing of knowledge and information, and give them greater financial flexibility –whether by providing credit to members in short-term difficulty, accessing loans from microfinance institutions (using their trees as collateral), or entering into a contractual agreement with a buyer like NFC that provides some payments in advance.

Finance isn’t just an issue for small-scale growers. Our afternoon session is a group discussion on the challenges of attracting finance into plantations in Africa, and some of the vehicles that have been set up to address this.

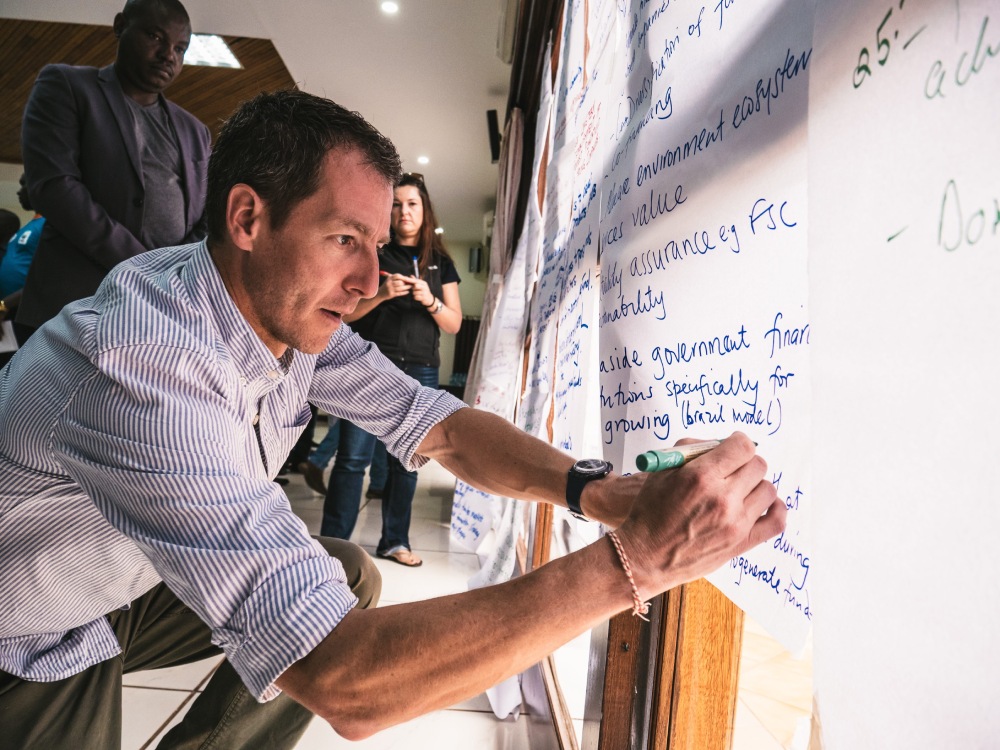

Representatives from several relevant finance initiatives have joined us on this study tour. They include Trillion Trees, a collaboration between WWF, BirdLife International and the Wildlife Conservation Society that aims to leverage funding for forest conservation and landscape restoration projects; the Land Degradation Neutrality Fund, which is aiming to raise US$300 million in public and private finance to rehabilitate degraded land; Tree Fund, which is being developed by The Nature Conservancy to channel investment into planting trees in the right places across Africa; and Criterion Africa Partners, a private equity firm that invests across the forestry sector value chain in sub-Saharan Africa.

These represent a wide range of potential finance sources – from commercial investors expecting high returns, to private impact investors and public sector development banks looking to balance financial returns with social and economic ones, to grants.

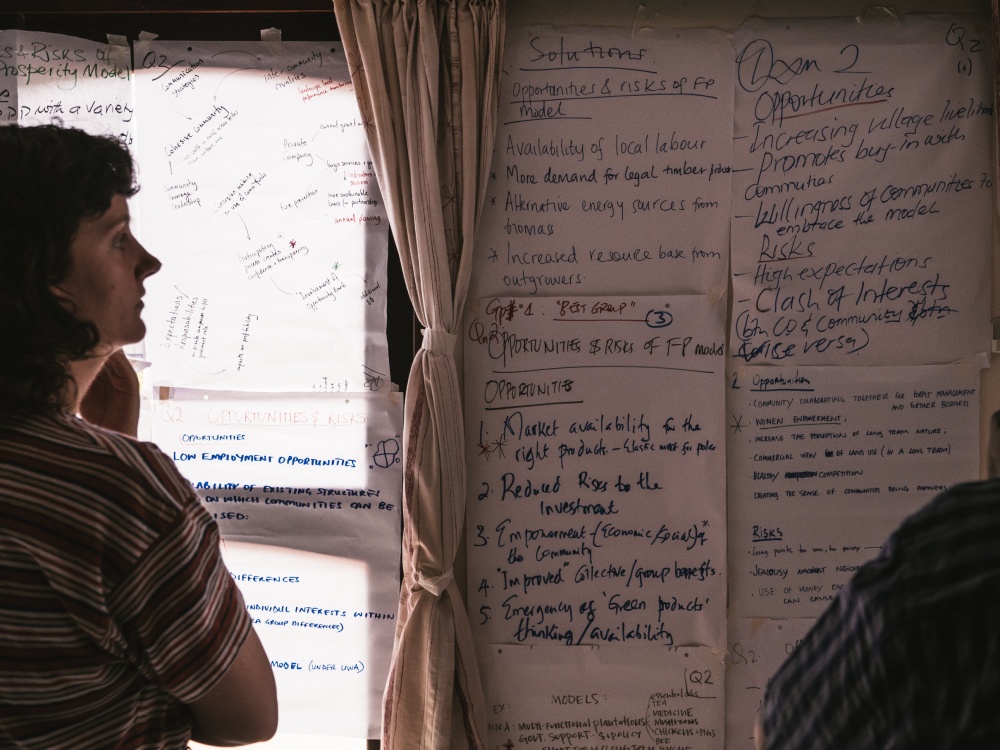

It is, of course, far too big a topic to cover in an afternoon, but there’s a general agreement on the need for more partnerships – between public and private sectors, NGOs and communities – that can attract a blend of different types of investment.

The other phrase that repeatedly crops up is “patient capital” – from investors who don’t expect short-term profits but are willing to wait for greater long-term results. Much like successful outgrowers really.